In cybersecurity, some of the most interesting work happens outside of responding to alerts or blocking connections. It’s in the quiet work of studying how attackers operate, learning from breaches reported by others, and digging into your own data to uncover things your monitoring tools may have missed.

That’s what threat hunting is about: going on the offensive to find the adversary who may already be in your environment, looking for their next payday.

What Do I Mean by “Threat Hunting?”

Think of your network like your home. Locks on the doors and windows (firewalls, antivirus, IDS) stop most intruders. But a skilled burglar might pick a lock, slip in through an unlocked window, or even walk in with a stolen key. Once inside, they don’t smash things – they move quietly, rifling through drawers and leaving little trace.

Threat hunting fills that gap. Instead of waiting on alerts, hunters build hypotheses about how an adversary might behave and then actively test those ideas against available data. It is structured, data-driven work focused on behaviors rather than signatures.

More importantly, threat hunting is a mindset: one that values curiosity, persistence, and the willingness to question assumptions. Every hunt – whether it uncovers malicious activity or not – improves understanding of your environment and strengthens defenses against evolving threats.

Key Concepts: IOCs and TTPs

When starting out in threat hunting, you’ll quickly run into two foundational terms: Indicators of Compromise (IOCs) and Tactics, Techniques, and Procedures (TTPs). Understanding the difference is critical because it shapes how you hunt.

Indicators of Compromise (IOCs):

IOCs are the digital “breadcrumbs” adversaries leave behind. They can be:

- File hashes of known malware samples

- IP addresses used as command-and-control (C2) endpoints

- Domains or URLs linked to phishing kits

- Registry keys or filenames associated with persistence mechanisms

These are valuable for detection because they’re concrete and easily matched in data. But the downside is that they’re also fragile. An attacker can recompile malware to change the hash, spin up a new IP, or register a fresh domain in minutes. IOC-driven hunting often turns into a game of whack-a-mole.

Tactics, Techniques, and Procedures (TTPs):

TTPs are the behaviors of adversaries, and they map directly into frameworks like MITRE ATT&CK. They operate on three levels:

- Tactics: The why – the adversary’s goal (e.g., initial access, lateral movement, privilege escalation).

- Techniques: The how – specific methods to achieve the goal.

- Procedures: The details – the exact commands or scripts used (e.g., running procdump -ma lsass.exe).

TTPs are more resilient for defenders to focus on. While an attacker can swap an IP address instantly, they can’t as easily abandon their need to dump credentials, move laterally, or persist in an environment. Hunting for TTPs means you’re looking at the behaviors that underpin the attack itself, not just the exhaust it leaves behind.

The PEAK Framework

Threat hunting isn’t about running random queries until something looks suspicious – it requires structure. One practical framework for approaching hunts is PEAK: Prepare, Execute, and Act with Knowledge.

- Prepare:

This phase is about defining what you’re hunting for and building context. It starts with a hypothesis. For example:- Hypothesis: “Attackers may be using unauthorized remote administration tools on endpoints.”

- Supporting knowledge: Remote tools like AnyDesk or TeamViewer might show up in process creation logs or network traffic.

Preparation also means understanding your data. Which logs do you have? Where are the blind spots? What does “normal” look like for your environment? Without a baseline, you won’t recognize the anomalies.

- Execute:

This is the investigation phase. You translate your hypothesis into queries and search across your data sources. The goal is not only to confirm or refute your hypothesis but also to learn more about the behaviors in your environment. - Act with Knowledge:

Once you’ve executed your hunt, you need to turn findings into action:- Escalate confirmed activity to incident response.

- Write new detection rules or dashboards.

- Document baselines and anomalies.

- Share findings with your team to improve collective knowledge.

- Even a hunt that turns up nothing isn’t wasted – knowing that certain activity is not happening is valuable context for future hunts.

Types of Hunts

There are three common styles of hunts, each serving a different purpose:

- Hypothesis-driven:

Starts with a focused question. Example: “Are attackers attempting to brute-force service accounts?”- These hunts are great for validating intelligence or testing assumptions about adversary behavior.

- They often rely on known TTPs and can be directly mapped to MITRE ATT&CK.

- Baseline (exploratory):

Focuses on establishing what “normal” looks like in your environment, then flagging deviations.- Example: A user who typically logs in between 8am–6pm suddenly authenticates at 3am.

- This type of hunting is especially useful in environments with little historical visibility – it builds the foundation for later hunts.

- Model-assisted (statistical/machine learning):

Uses anomaly detection, clustering, or statistical baselining to highlight suspicious activity.- Example: Detecting unusually long network sessions that may indicate data exfiltration.

- While these hunts can uncover subtle threats, they require clean data and careful interpretation – false positives are common if the models aren’t tuned.

A mature hunting program blends all three: hypothesis-driven hunts to test specific threats, baseline hunts for context, and model-assisted hunts to scale beyond what humans can do alone.

The Pyramid of Pain

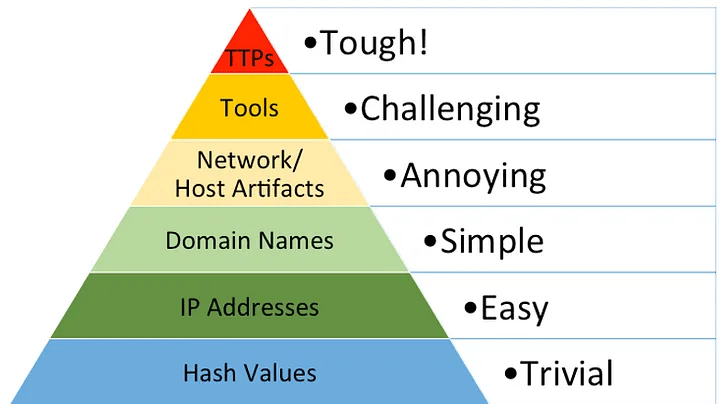

David Bianco’s Pyramid of Pain is a visual model that explains how much “pain” you impose on attackers when you detect and respond at different levels of indicators.

- Hashes: Lowest level. Blocking a malware hash is trivial for attackers to bypass – recompile and move on.

- IP Addresses: Slightly more effort, but attackers can rotate infrastructure or use VPNs/CDNs.

- Domains: Harder still – new registrations and DNS updates take more time and money.

- Network/Host Artifacts: Observable patterns such as unusual URI paths, command-line arguments, or registry modifications. Altering these requires real operational changes.

- Tools: Blocking tools like Cobalt Strike or Mimikatz forces adversaries to acquire or build alternatives, costing significant effort.

- TTPs: The top of the pyramid. Detecting behaviors like credential dumping, lateral movement, or data staging forces attackers to completely rethink how they operate.

The closer your hunts get to the top of the pyramid, the more resilient your detections become. IOC hunts at the bottom are quick but shallow. TTP hunts at the top are harder, but they impose maximum cost on adversaries and give defenders the longest-lasting advantage.

What Next?

Threat hunting isn’t about waiting for alarms to sound – it’s about taking the initiative to uncover adversary behavior before it turns into an incident. By understanding the difference between IOCs and TTPs, applying a structured approach like the PEAK framework, and aiming your hunts higher on the Pyramid of Pain, defenders can shift from reactive response to proactive detection.

Hunting sharpens both technical skills and organizational defenses. Even when a hunt doesn’t uncover active compromise, it adds valuable knowledge about what “normal” looks like in your environment and where your blind spots may be. Over time, that knowledge translates into stronger detections, faster response, and more resilient defenses.

This post introduced the foundations of hunting – why it matters, the concepts that guide it, and the frameworks that shape it. In part two of this series, I’ll expand on where to find IOCs and TTPs, and show how to apply them in practical hunts. We’ll walk through basic hunting examples to demonstrate how these concepts come together in real-world analysis.